America’s Workers Are Under Attack—And The Culprit Is the President

Professor Jeremy Ney exposes how Trump’s extremist agenda, corporate greed, and systemic racism are fueling a labor crisis.

Periodically I publish guest voices who are scholars in their field. Today I’m publishing a powerful and important piece by Professor Jeremy Ney from the Columbia School of Business, on the current labor crisis Americans are experiencing. A crisis further exacerbated by the Trump regime’s extremist policies targeting Black people, Latinos, migrant workers, and now South Korean workers. Trump’s recent ICE raids in South Carolina place another 8500 high paying jobs at risk, while jeopardizing hundreds of billions in income for the American people. But the problem goes much deeper, and resolving it won’t be easy. How bad is the situation exactly? Professor Ney explains. Let’s Address This.

Bio: Jeremy Ney is the author of the American Inequality newsletter, a professor at Columbia Business School, and a former macro policymaker at the Federal Reserve. He is publishing a forthcoming book on opportunity and inequality in America.

The U.S. is experiencing a labor crisis. On Friday, the U.S. announced it added only 22,000 jobs in August, raising unemployment to its highest level in 4 years. 870,000 U.S. workers earn at or below the minimum wage. 20-40% of job listings are “ghost jobs” - posted by a company to make it seem like they are growing with no real intention to ever hire for the role. Union membership has fallen to an all-time low, dropping by half from its 1983 peak. 300,000 federal workers have lost their jobs in the past 9 months, with Black women being among the hardest hit. Workers aged 22-25, saddled with student debt, are struggling to find jobs in this era of explosive AI growth. With Labor Day in the rearview mirror, what is America’s path forward?

This national narrative, however, conceals a greater challenge occurring in communities. Research from American Inequality reveals that depending on where a person lives, their likelihood of being unemployed can rise by 3x, their chance of working a minimum wage job can increase 3x, and their bargaining power erodes by 10x due to employer concentration.

Unemployed in Mississippi

Mississippi is a prime example of labor inequality in America. 41% of Mississippi workers are considered low-wage, the highest share anywhere in America. But Jefferson County has the worst unemployment rate in the state and in 2020 claimed the title of the fourth worst unemployment rate in the nation. Today, unemployment remains triple the national average, workers earn just half the U.S. average in a typical week, and the county has been shedding employers for decades as the population has dropped dramatically. 29% of Jefferson County residents live in poverty, almost triple the national poverty rate.

Without jobs, calamity strikes. Homelessness has started rising because people don’t earn enough to afford their rents. Public health deteriorates because without jobs many people don’t have insurance. Nearly one-third of residents live on food stamps and so people frequently break into homes to find food for their children. The incarceration rate in Jefferson is 19x higher than the national average.

“There are no jobs here,” said L.C. Whistle, a 60-year old Jefferson County native who collects and sells old car parts. “You might make enough to live, if that, but you aren’t going to get rich.” He remembers when an auto dealership moved away and how the county struggled to attract new industries in the wake of its departure. Residents have three options: Leave, take a minimum wage job, or find informal work.

Black Workers and Mothers Face the Biggest Labor Barriers

The Black U.S. unemployment rate is consistently double the White unemployment rate. When Black Americans are employed, they earn 76 cents on the dollar relative to White workers, worse than the gender pay gap of 85 cents. One of the leading causes of the Black-White unemployment gap is the high incarceration rate of Black Americans. In 2018, formerly incarcerated individuals were unemployed at a rate of 28%.

Women continue to face barriers in the workforce. An August 1 BLS report showed that in the first 8 months of the year, a net 212,000 women left the workforce while 44,000 men entered it. The labor force participation rate of women aged 25-44 living with a child under five fell nearly three percentage points from 69.7% to 66.9%. Researchers pointed to a decline in workforce flexibility that disproportionately hurt women who bore the burden of family childcare. Compared with pre-pandemic, the number of people working part-time or not in the labor force due to the cost of childcare has increased 21%. More than 60% of families living in poverty have to forgo work to stay at home and care for their children. When 2.2 million women left the labor force at the beginning of the pandemic to care for their families, many did not return. The same was not true for men.

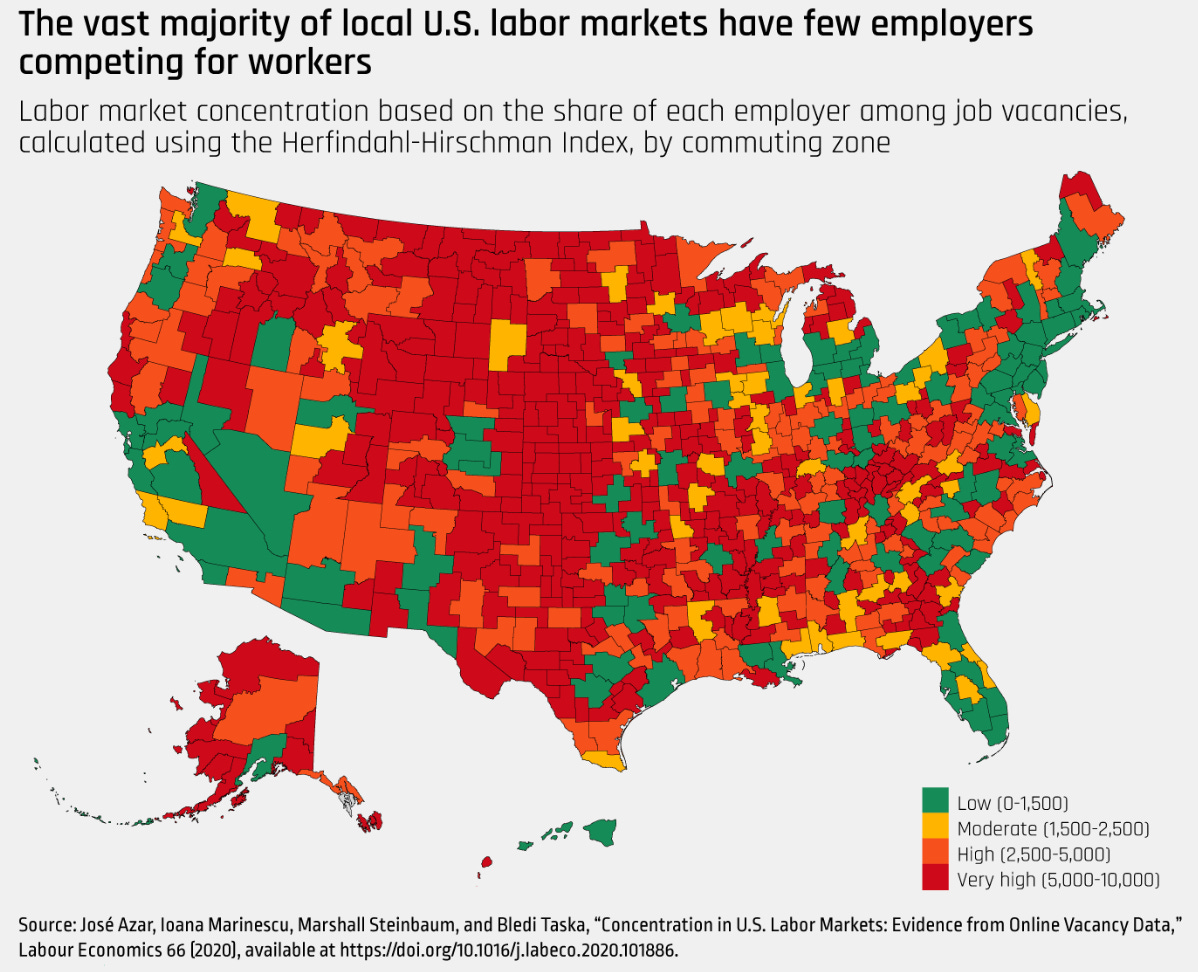

Labor Market Concentration in the Midwest Hurts Workers

75% of U.S. industries have consolidated significantly over the last century, making companies more powerful and is hurting workers due to lower wages. As one MIT economist has pointed out, industry consolidation has increased rapidly since the 1970s, limiting the bargaining power of workers and driving income inequality. “I found that when big buyers consolidate, the increasing power of large buyers explains around 10% of wage stagnation since the late 1970s,” said Nathan Wilmers.

These high rates of concentration are most common in the midwest. Indiana, Iowa, and Wisconsin have all experienced the highest consolidation of manufacturing employers relative to the national average over the last 30 years. Not only did this drive down the total number of jobs in these regions, but these states have all also seen declining union membership, which is frequently a bulwark against rising employer power. Union jobs to offer wages that are on average 11% higher than non-union jobs, even controlling for industry and seniority.

The Path Forward

Three solutions point toward a fairer labor market. First, the Federal Reserve can use its existing authority under the Humphrey-Hawkins Act to place greater emphasis on lowering unemployment among Black workers. Second, more companies should expand remote and hybrid work, a change that eases burdens on parents—especially mothers. The World Economic Forum found that women’s applications to remote jobs rose by 20% and their acceptances rose by 10% since March 2020. Finally, historically disadvantaged communities like Jefferson County need more employer options, which requires incentives from the local, state, and federal government to draw new employers there that can pay a living wage.

Be sure to subscribe to Professor Ney's "American Inequality" newsletter.

Qasim here. My gratitude to Professor Ney for sharing this critical data and helping make sense of these trying times. Please share your comments on your experience navigating this volatile job market, and feel free to leave any questions you have for Professor Ney. He will do his best to answer as many as possible. And be sure to subscribe to Professor Ney’s “American Inequality” newsletter, linked above.

Thank you for this analysis. Jobs are moving in the direction of an incarceration-driven economy. Prison culture destroys the lives of everyone involved in it and creates more problems than it solves. Discourage people from working in this sector.

Recession first!!! Which is happening right now, by the way! Great Depression next! Blame Trump and his administration! Democrats need to shut the government down when the next votes happen! Schumer, take your head out of your arse!